These notes on Race with the Devil were written by Josh Martin, PhD student in the Department of Communication Arts at UW-Madison. A new 4K DCP of Race with the Devil will screen in our "Action Vehicles" series on Friday, July 19 at 7 p.m. in our regular venue, 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave.

By Josh Martin

In Susan A. Compo’s biography of Warren Oates, the iconic star of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), she recalls a bizarre story from the production of Race with the Devil, Jack Starrett’s 1975 genre-bender. With Oates and co-star Peter Fonda eager to appear in “a sure-fire moneymaker,” the former agreed to lead the project — tacking on the additional request of having producers furnish him a new RV. Preparing to shoot the film in the Texas winter, Oates loaded up the vehicle with friends, including pal Harry Dean Stanton, for a series of drives through the southwestern United States. During these drives, Oates and his companions took heavy doses of psychedelic drugs. Soon, they reported experiencing close encounters with extraterrestrial life — encounters witnessed only by those under the influence. In Compo’s account, Oates associate Dean Jones recalls that “they all saw a UFO'' on the drive to San Antonio, though Bob Watkins, another friend, acknowledged that they “were hallucinating to some extent.” This countercultural debauchery may seem irrelevant to the eventual production of a major motion picture, but it is in these conditions — an anxious, drug-addled state, blending genuine fear of the unknown and jovial absurdity — that the equally paranoid and unusual Race with the Devil came to exist.

Starrett’s film features an elevator pitch that practically jumps off the page. Four years after Fonda and Oates first appeared together in The Hired Hand (1971), the former’s directorial debut, the duo reunited for a road movie-turned-horror picture about two motorcyclists who stumble upon Satanic rituals deep in the heart of Texas. If this concept seems ripe for campy thrills and witchy kitsch, the tone that the filmmakers strive for proves more sinister, a mood that is immediately evident from the opening credits. As the camera tilts up on the dividing lane of a dark, empty highway, storm clouds gather ahead, clustered around a lone tree as discordant music sets the atmosphere of unease. The clouds change in color to a bright, blood red, with the space eventually abstracted, enveloping the spectator in this frightening universe.

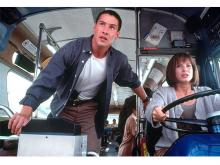

Despite the early preview of a menacing mood, Race with the Devil more accurately simulates the steady deterioration of a bad trip. Fonda and Oates star as Roger and Frank, respectively, two friends and speed enthusiasts who are taking their first much-needed vacation in a long time: a January jaunt to Aspen for some winter skiing. Roger and Frank are joined by their wives, Alice (Loretta Swit) and Kelly (Lara Parker), as they pack into Roger’s brand spanking-new $36,000 motorhome, equipped with all manner of bells and whistles. The RV enables the kind of independence and solitude that the men are looking for, with Roger exclaiming, “We don’t need anything from anybody! We are self-contained, babe.” But more crucially, the road trip gives Roger and Frank an opportunity to relax, to bond with one another, sharing sentimental remarks over drinks and racing their bikes in the Texas desert. Seemingly in an attempt to push the opening credits sequence out of our minds, the film plays up the tranquility of this escape – the sense of calm that washes over our lead characters.

Stopped for the night in an empty valley, Roger and Frank’s boozy soiree is rudely interrupted when a tree is lit on fire several hundred feet from them. Their interest piqued, the buddies look through a pair of binoculars to see a strange ritual, featuring men chanting and wearing bizarre robes. The tone of the film does not immediately shift, with Starrett teasing the potential for comedic hijinks in this peculiar discovery. Yet as the ritual continues, the film initiates an accelerated editing rhythm, with the montage becoming more pronounced in tandem with the demonic chanting. But this is no hallucination: the frenzied cutting culminates in the sacrificial murder of a young woman, an act of violence that sends Roger and Frank into a full-blown freakout. Spotted by the cult, they find themselves on the run, the good vibes of their vacation thwarted.

Race with the Devil plays on the fears of the post-countercultural moment, on a diffuse sense of paranoia directed at the dark side of peace, drugs, and free love. The sheriff, when informed of the ritual murder, grumbles that a “bunch of hippies moved into the area… stuffed garbage up their nose and into their arm,” thus making the town an uglier place. Though Fonda’s Frank is skeptical that the murder is “hippie”-related, the film draws on this constellation of interrelated cultural pressure points, engulfing post-Manson mania, ritual violence, and Satanic panic.

Equally essential to this concoction of mid-1970s anxiety is a fear of rurality, of what horrors may lurk deep within the forgotten, neglected corners of America’s vast landscape. Race with the Devil concocts a disturbing ambience around the denizens of these small Texas towns, transmitting the unshakable feeling that everyone is in on the plot, out to punish the city folks for their invasion on this territory. Compo notes that the screenplay, written by Lee Frost and Wes Bishop, was “inspired” by John Boorman’s 1971 classic Deliverance, another tale of friends who get a little more than they bargained for with some nefarious locals on their vacation. And while the slasher is not a sub-genre in play here, Race similarly recalls Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), particularly in the dusty spaces and open Texas fields where our horror takes place.

Amid this swirl of influences and cultural concerns, the film had a somewhat tumultuous production, which Compo’s book carefully recounts. Co-screenwriter Frost was the original director, but 20th Century Fox became weary of the unpredictable Oates, Fonda, and Bishop’s frequent changes to the dialogue, eventually placing Starrett in the director’s chair as a steadying force. After this change, production settled into a groove, resulting in a profitable endeavor. In one famed anecdote, producer Paul Maslansky solicited the work of “Satanists and black magic experts” as extras, providing a purported verisimilitude to the far-fetched picture.

While writing on Race with the Devil often draws comparisons to Rosemary’s Baby (Polanski, 1968) and The Exorcist (Friedkin, 1973), the particularities of the cult’s Satanic plot here are functionally irrelevant. What Starrett’s film instead offers is a feeling of suspicion — an uncertainty that builds to a surreal sense of entrapment and terror. In this manner, one feels a stronger kinship between Race with the Devil and the uneasy vibes of films like The Wicker Man (Hardy, 1974) or Messiah of Evil (Huyck and Katz, 1973), especially as Starrett’s picture reaches its climax. Though Maslansky believed that the ending “sucked” and co-star Lara Parker lamented its “meanness,” the unsparing, slow-motion conclusion is the perfect validation of the film’s paranoid logic, with all the distressing incidents and unresolved threads coalescing into a nightmarish series of images. Race with the Devil may have its fun — in its intense chase sequences and its buddy film rhythms — but a feeling of inescapable doom lingers once the credits roll.