This essay by Leo Rubinkowski, Graduate Student and Teaching Assistant in UW Madison's Communication Arts Department, discusses the first two features of Leos Carax, Boy Meets Girl and Mauvais Sang, both of which star Denis Lavant. The two films screen respectively at the UW Cinematheque on Saturday, October 4 and Saturday, October 11.

It is probably safe to assume that before the appearance of Holy Motors (2012) on US screens, most of that film’s American viewers (including yours truly) were more or less unfamiliar with Leos Carax. Helped along by the usual festivals, but surely benefitting from the ubiquity of online film criticism (Carax’s previous feature, Pola X, came out in 1999), Holy Motors performed respectably despite a very limited release in art houses and independent theaters. It is tempting, therefore, to fold renewed interest in Boy Meets Girl (1984) and Mauvais Sang (1986) neatly into the success of his latest work. Why else should Paris-based distributor Carlotta Films have inaugurated their US office with the first two features of an inarguably distinct, though commercially marginal, figure of contemporary French cinema?

In the mid-1980s, though, Leos Carax was not a pre-sold brand. To make sense of the new director, critics tended to look backwards, recognizing that what is idiosyncratic of Carax’s stories and style is also unabashedly familiar.

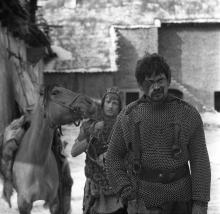

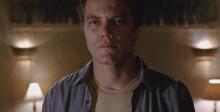

In Boy Meets Girl, Carax tells the story of Alex (Denis Lavant) and Mireille (Mireille Perrier), one an aspiring filmmaker recently dumped by his girlfriend and the other a suicidal actress whom Alex overhears breaking up with her boyfriend through an apartment intercom system. Despite not having actually seen Mireille, Alex falls in love with her. Later, the two meet at a dinner party and spend the night together until chance intervenes (again).

In contrast, Mauvais Sang is a heist picture. Marc (Michel Piccoli) must plot a crime to pay off a gangster known as “The American.” To help with the job, he brings on Alex (Lavant), the son of a recently deceased colleague. Alex falls in love with Marc’s lover, Anna (Juliette Binoche), who keeps Alex’s romantic overtures in check. Of course, the eventual robbery does not go as planned. Guns are fired, agreements are broken, a hostage is taken, and before long, all lines of action and feeling intersect in Alex’s dramatic final moments. (According to Carax, he stole several plot elements from a Raoul Walsh picture, Salty O’Rourke [1945].)

Following its run at the 1985 New York Film Festival, Vincent Canby mused of Boy Meets Girl, “one recognizes a bit of Jean-Luc Godard here, something of François Truffaut there, and every now and then one hears what may be the faint, original voice of Mr. Carax trying to make himself heard around and through the images of others.” Canby’s observations were not unique. More than a few critics treated Carax as a continuation of the French New Wave’s spirit, and the influence seems evident in both Boy Meets Girl and Mauvais Sang in many ways. When Alex and Mireille talk for the first time in Boy Meets Girl, can we imagine Carax is not quoting Vivre sa vie (Godard, 1962)? Mourning the vicissitudes of youth and l’amour fou, will Alex go to Antoine Doinel or Patricia Franchini for sympathy? And speaking of fated love, whose chemistry was more obvious: Michel and Patricia’s in the half-hour bedroom sequence from Breathless (Godard, 1960) or Alex and Anna’s during their all-night vigil in Mauvais Sang? Of course, the ties that bind Carax to the New Wave run deeper than mere situation. In Mauvais Sang, for instance, foreboding strings, primary colors, abrupt inserts, and flat stagings all call to mind similar stylistic elements at play in Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965).

However, it would be misleading to think that Boy Meets Girl and Mauvais Sang are the products of a director working after his time. As likely as they were to praise Carax as a reincarnation of the past, French critics in the mid-1980s also associated him with a contemporary trend in French cinema unofficially dubbed le cinéma du look. Like contemporaries Luc Besson (Subway, 1985; Nikita, 1990) and Jean-Jacques Beineix (Diva, 1981), Carax’s non-naturalistic approach to aesthetics seems to draw heavily from the conventions of television commercials, music videos, and fashion photography. Tight depth of focus, lighting set-ups that cause faces and props almost to glow while drowning backgrounds in shadow, and framings that militantly organize attention to the mise-en-scène all contribute to a visual resonance atypical of most films, including those of the New Wave directors. If, as Alex observes in Mauvais Sang, “You need to feed the eyes for your dreams,” many a night of sound sleep must have originated in the minds of Leos Carax and his director of photography, Jean-Yves Escoffier.

This dream-like quality is likely the feature that will impress viewers most during a first viewing. In part, this is a consequence of Carax’s style. Editing, sound, cinematography, and mise-en-scène all conspire to suggest that the story is happening out of focus, out of earshot, or outside the frame. Mystery suffuses the look and sound of Boy Meets Girl and Mauvais Sang. In the best surrealist tradition, though, Carax allows that mystery – that fantasy – to tear at the seams of his story worlds. Indeed, it is as if Alex (both of them), Mireille, Marc, Anna, Hans (Hans Meyer), and Lise (Julie Delpy) occupy a universe not identical to our own, but adjacent, where the day-to-day vies for relevance with the grandiose and the subtly absurd. A man and a woman lock in a passionate embrace, and then begin to rotate in place like mannequins; a passer-by tosses loose change for their trouble. A bed retains only the barest signs of a would-be lover: a cigarette, a tissue, a single hair, and the impossible indentation of her curled body. A desperate criminal takes an equally desperate hostage. A wall of cupboards reveals a single, chipped teacup. The radio plays “the very tune that [is] humming inside your head.”

This last moment may be the most important, because it responds best to the tragedy of viewing Leos Carax’s work. There is no way to freeze Lavant mid-stride, capture Piccoli and Serge Reggiani mid-scuffle, or halt Binoche mid-stretch. The intensity of despair in Mireille’s shorn hair will always be locked away on film. The experience resonates, but that resonance is a shadow. Nevertheless, when the feeling of loss is too great, when the cement in our stomachs begins to harden, there’s the smile of speed…and there’s David Bowie.